The Daily Churn

Third largest dairy producing country embraces sustainability

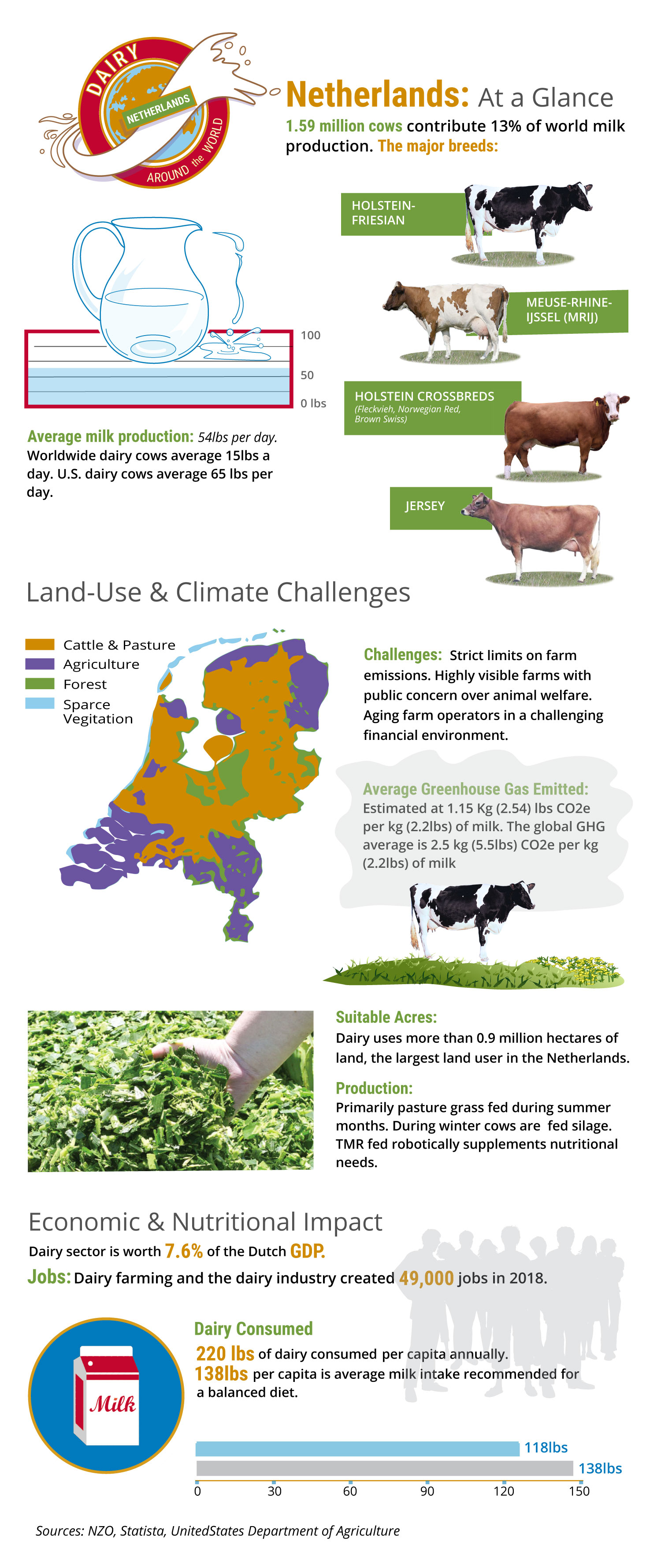

Dairy is “in the genes of the Dutchman,” says 64-year-old Netherlands dairy farmer Ad van Velde.

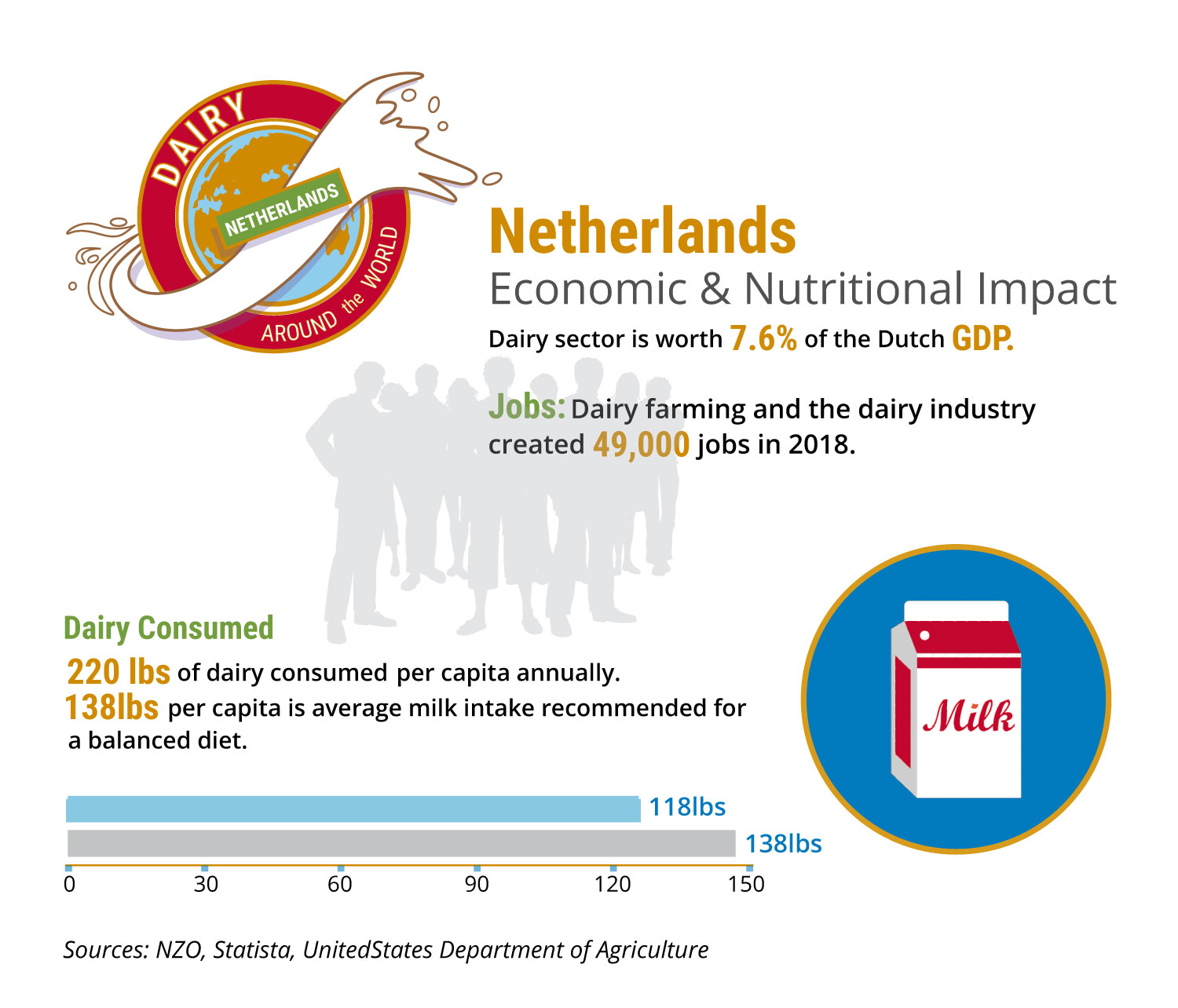

So, it comes as no surprise to him that the Netherlands — just twice the size of New Jersey — was the number three dairy exporting nation in the world in 2019.

“We produce a lot of milk in the Netherlands in a small place and we export 65 percent of our milk,” van Velde says. “The Netherlands has to be in front when we talk about climate neutrality, animal health, antibiotic reduction, cow comfort and all the things society looks at. We have to be in the lead because we have a strong export position.”

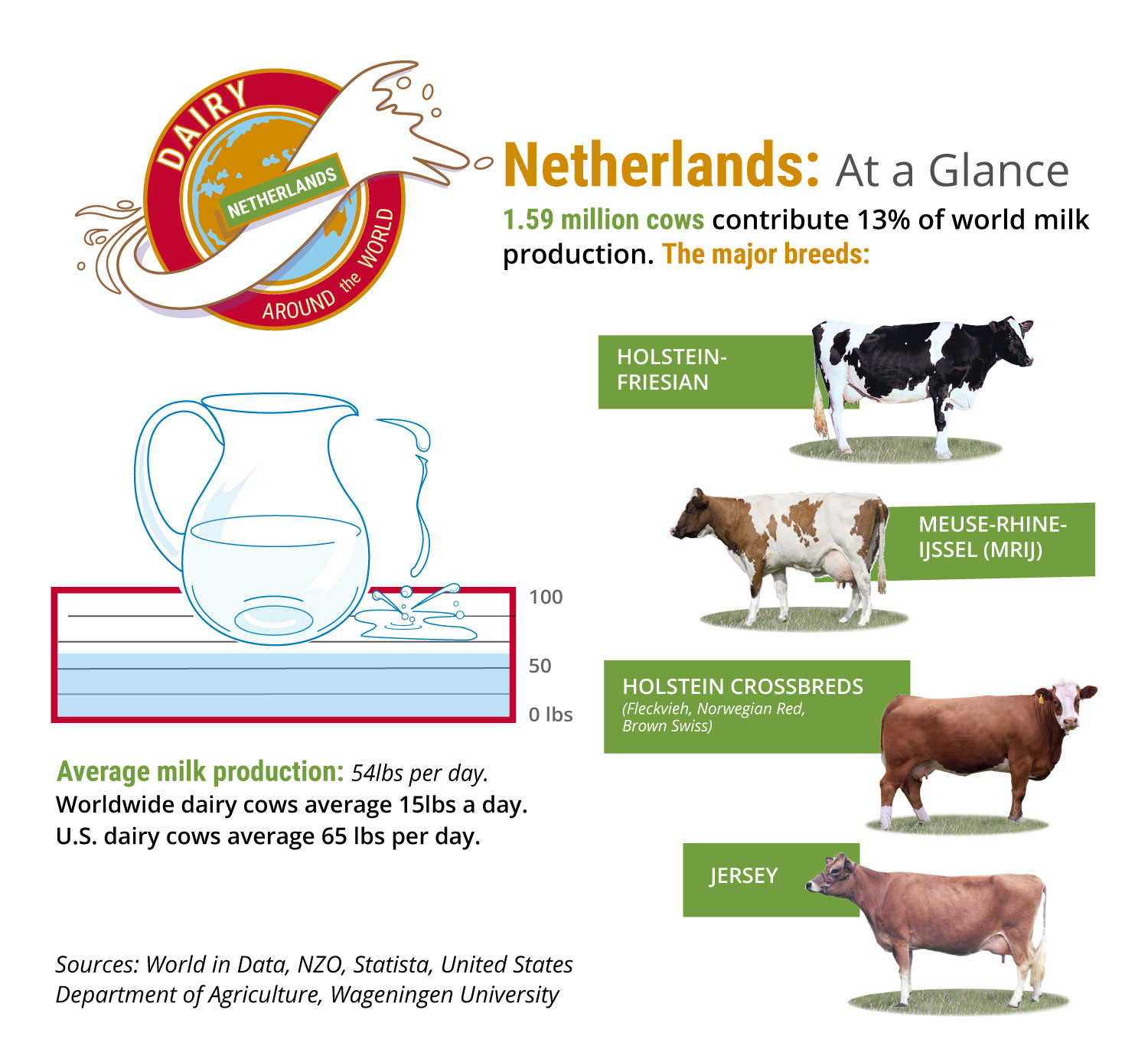

Dutch agriculture production, including horticulture, contributed 14 percent percent of the nation’s greenhouse gas emissions in 2016.

In response, the government capped on-farm emissions of nitrogen and phosphate, limiting farmers’ ability to grow their operations. In 2019, the country pledged to reduce total greenhouse gas emissions by 49 percent by 2030 (compared to 1990) and 95 percent by 2050.

Dutch consumers are also worried about cow welfare. Around 94 percent of European Union (E.U.) citizens believe it essential to protect the welfare of farmed animals, according to the 2016 European Commission Animal Welfare report.

Tensions came to a head in October of 2019 when thousands of Dutch farmers created 700 miles of traffic jams driving their tractors to The Hague, the Dutch administrative capital city.

They were protesting a proposal to slash Dutch livestock farming operations in half to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. While that idea was dropped, Dutch agriculture — especially dairy farming — continues to operate under close regulatory and consumer scrutiny.

To meet these challenges, the Netherlands’ dairy supply chain is increasingly turning to technology and collaboration, to improve operations, while sharing their achievements, van Velde and other Netherlands’ dairy experts told the Daily Churn.

Classic dairy scene in The Netherlands

State of dairy in The Netherlands

Like other nations with mature dairy sectors, the number of Dutch dairy farms is shrinking while the average herd size increases.

In 2000, there were almost 30,000 dairy farms in the Netherlands and 1.5 million total cows, but by 2020, there were just under 16,000 Netherlands dairy farms with 1.59 million total cows, according to Statista. The average herd size in 2020 was 101 cows. By comparison, the U.S. had 9.3 million dairy cows in 2020 with an average dairy herd size of 297 cows.

Wageningen University expects the trend to continue with an additional 30% reduction in dairy farms by 2030. While cow numbers are expected to decline to 1.48 million total, individual production is predicted to increase by 4%. Average herd size could reach 139 cows.

Many dairy farmers in the country were expanding operations in anticipation of the E.U. milk quota system expiring in 2015, says Daniëlle Duijndam, a dairy analyst for RaboResearch Food and Agriculture.

But then the government imposed strict new manure management regulations to limit dairy growth and keep the country in line with EU-imposed emissions caps.

“They prepared for more freedom with the end of the milk quota season,” says Duijndam, “and then they got a new quota system.”

The Netherlands introduced legislation in 2016 requiring all dairy farms with a surplus of manure to process it off-farm; if they wanted to grow their herd size, they had to acquire more land for manure disposal.

In addition, a new system of phosphate rights started in 2018, limiting production in the Dutch dairy sector. Dairy farmers were told to reduce their herds to 2015 sizes or face fines.

This came after years of increasingly restrictive environmental mandates leveraged against Dutch agriculture, according to a 2017 World Bank Group.

These laws resulted in a series of cap and trade policies for manure rights, buy-out schemes to reduce the number of pork, poultry and beef farms and restrictions on the amount, timing and method of manure application on fields.

In addition, farms located close to designated protected nature areas might turn into extensive buffer zones. Duijndam says this challenges many farmers to choose a strategy: “Will you adapt to a more extensive production system, relocate to stay in business or stop farming?”

Dutch dairy farmers recognize the need for sustainability and are willing to improve, says Duijndam, but rather through innovation and entrepreneurship than government mandates.

“Everyone knows that things need to change, but (farmers don’t like) the government saying you have to do this,” she says. “The farmers want room for entrepreneurship. They want to innovate.”

Despite the challenges, dairy remains a beloved part of the Netherlands’ culture and landscape.

Dairy is part of the Dutch landscape

Agriculture provides a visual background of the Netherlands, with its iconoclastic windmills, tulip fields and famous black and white Holstein-Friesian cows grazing lush green pastureland lined by dikes.

But that also means the Dutch population expects farms to meet their expectations — especially relating to cow welfare, says van Velde.

That’s why visitors are welcome at his 220-cow, 90-hectare farm, Hunsingo Dairy.

Located just five miles from the Wadden Sea in the picturesque northeast region of Groningen Province, van Velde’s dairy is often visited or passed by tourists, like most Dutch dairy farms.

He uses that opportunity to educate.

The Netherlands is the fifth most densely populated country in the E.U., with 511 inhabitants per square mile.

Meanwhile, as much as 70% of the country’s land is used for agricultural production, with animal densities among the highest in the world, according to the World Bank.

By comparison, there are 93 residents per U.S. square mile on average and agricultural lands make up 44% of the land base.

Van Velde admits it can be frustrating when city residents and politicians make decisions for farmers. With 17 million Dutch citizens, he says, sometimes it can seem like there are “17 million farmers” telling him how to farm.

“People living in Amsterdam, they make $100,000 a year and they buy organic food and. They decide about agriculture? That is frustrating to me,” he says.

This is why van Velde believes it is so important to engage with and educate the public. When farmers share what they do and why they do it with consumers, he says, then they understand and appreciate the work.

“We have to be transparent.” he says. “For the Dutch consumers but also for consumers from all over the world.”

Leading the world in dairy innovation

Peter van Wingerden knows a thing or two about the keen public interest in Dutch dairy farming.

Van Wingerden hosts a constant stream of tourists, education groups and press at the Rotterdam Floating Dairy, the world’s first “floating dairy” housing a herd of 40 dairy cows on a three-story barge. Its home base is the Netherlands’ famous Rotterdam port.

“Every month, there are groups (visiting) from all over. U.S. to Japan. Students, farmers, city developers, ministers, European Parliament,” van Wingerden says. “They’re all searching for the same question. How do I feed my city, my country in a sustainable, climate adaptive, prepared way?”

Everything is automated on the floating farm. High-tech milking machines milk the cows. Their feed comes on an automated belt. Manure is managed by robots and separated into solids and liquids and used as compost and fertilizer by Rotterdam parks.

By this October, van Wingerden hopes to start construction on a second barge, a vertical farm that will produce vegetables and herbs. Manure from the floating dairy farm will be used to fertilize the new vertical farm and the leftovers from the harvest will be fed to the cows.

The floating dairy is an extreme example of tech innovations originating from the Dutch dairy sector, but it is far from the only example.

International companies like Lely, founded in the Netherlands in 1948, are global leaders in dairy tech. Lely builds automated milking and feeding systems, robotic manure management and automated cow health tools like overhead mounted rotating brushes that keep cows clean and relieve itchy skin.

Hanskamp AgroTech, another Dutch-founded dairy agritech company, invented the novel “Cow Toilet,” which separates urine from feces and prevents volatile ammonia gases from being released into the atmosphere.

Van Velde has had four milking robots on his farm since 1988. The robots plus contracting out fieldwork helps him avoid Netherlands’ notoriously high labor costs. He pays about €35 ($42) an hour and runs his farm with less than two employees.

Dairy farming is part of the Dutch landscape.

Incentivizing farmers to improve Dutch dairy sustainability and cow welfare

Committed to being proactive about environmental and consumer concerns, van Velde has implemented a variety of practices and technology that improve his operations.

In addition to installing solar panels that power his farm and the nearby village, he rotates fields with a neighboring crop farmer, spreading some of his manure there too. His cows also have pasture access during the summer months; when they return to the barn, they rest on a composting bedding system. And he has reduced artificial fertilizer use by 50% in 15 years.

There’s more. About 20 years ago, van Velde began actively cross-breeding his once prize-winning purebred Holstein-Friesian herd with other breeds to create a healthier, long-lived cow.

“I’m very enthusiastic about cross-breeding. What you get is a stronger cow,” van Velde says, noting that he doesn’t use hormones and is very close to going entirely antibiotic-free with his herd.

Meeting sustainability and cow welfare goals helps van Velde capture a premium for his milk.

Dairy processors like Friesland Campina, the 7th largest dairy company globally, are paying dairy farmers a premium for meeting sustainability certification measures.

Farmers must meet grazing access metrics, have no more than 10 cows per hectare, avoid unnecessary antibiotic use and provide other cow welfare and soil health improvements.

These supply chain incentives are different than organic certification, which Duijndam says is limited to maintain the high value of organic dairy products.

The dairy sector also works together to support and incentivize their peers.

One example of this? “Duurzame Zuivelketen” — the Sustainable Dairy Chain.

An alliance founded in 2008, the group represents approximately 70% of Dutch dairy farmers via LTO Nederlands, a Dutch farmer organization, and 98% of Dutch dairy processors, members of the Dutch Dairy Association (NTO).

The alliance focuses on improving cow health and welfare, climate-neutral grazing, environmental protection, and the preservation of grazing, according to a report from the Wageningen Economic Research, which monitors their progress.

Sustainable Dairy Chain

In 2019, the Sustainable Dairy Chain promised to meet aggressive emissions reduction goals by 2030, pledging to reduce greenhouse gases across the dairy supply chain by a total of 1.6 megatons of CO2 equivalent.

To achieve these gains, according to a report on a Climate-Sensible Dairy Sector in the Netherlands, they collaborate with dairy processors, the Dutch government, provincial authorities, the feed industry and social organizations to incentivize farmers.

Van Velde, whose family has farmed in the Netherlands since the 1800s, remains optimistic about the future of dairy farming — obstacles aside.

With a growing world population needing more food, he says, nations like the Netherlands (with their access to water, productive soil and the technical capabilities to pursue intense production on a small carbon footprint) will have a substantial role to play.

He advises young farmers to pursue a global education and worldview.

A world traveler himself, van Velde speaks with other dairy farmers and shares successes as president of Global Dairy Farmers, a worldwide network that includes industry partners.

He’s also seen, firsthand, the results of taking sustainability measures.

When van Velde started relying more on organic fertilizer, he doubted he could produce enough roughage for his cows. But he persevered, planting better pasture varieties and fine-turning his manure management out in the fields.

The results, he says, are visible.

“We have ditches around the farm and the water was always dirty,” says van Velde. “Now it’s clean.”

:: Images courtesy NZO and Hunsingo Dairy