The Daily Churn

South Africa’s dairy sector strives to shake off its past

Jeanet Rikhotso manages a herd of dairy cows in one of South Africa’s poorest provinces — the Eastern Cape.

She was recruited into the sector while in agricultural college, where she was mentored by Amadlelo Agri, an operator that invests in black-owned, community-led agribusinesses.

Rikhotso, who is now 33, showed an immediate aptitude and quickly went from being a student to being an employee and then manager of 800 milking cows — 95 of them her own.

This is not easily achieved in South Africa, where the state-owned Industrial Development Corporation (IDC) recently launched a $340 million fund to help Black farmers gain access to the tools they need to succeed.

Overall milk production soared 31% between 2009 and 2019, according to statistics provided to the Daily Churn by Milk SA, a non-profit promoting South African dairy.

But farmers are being squeezed by an intensely competitive, deregulated marketplace and worsening impacts of climate change-induced weather extremes, according to locals.

And then there are the leftover relics of apartheid.

“I’d like to believe I inspire other women,” Rikhotso tells The Daily Churn. “When they look at me they see I am doing it and they believe they can do it.”

Still, she adds, there is much more work to be done. “We haven’t brought as much change as we should to these communities.”

State of Dairy in South Africa

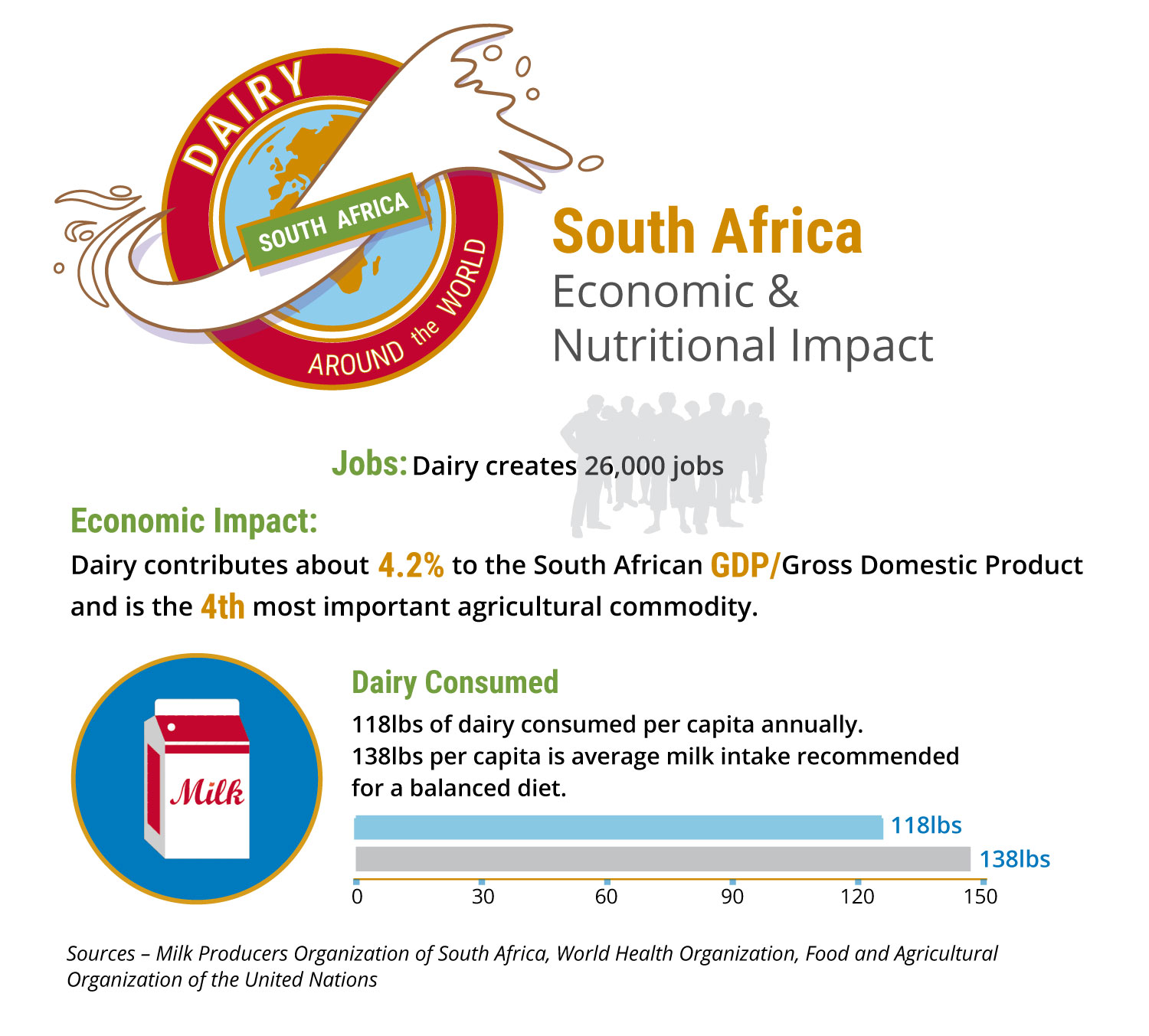

Despite its struggles, dairy is still the fourth largest agricultural industry in the country, Barbara Bieldt, market development and compliance service manager for the Milk Producers Organisation (MPO), told the Daily Churn.

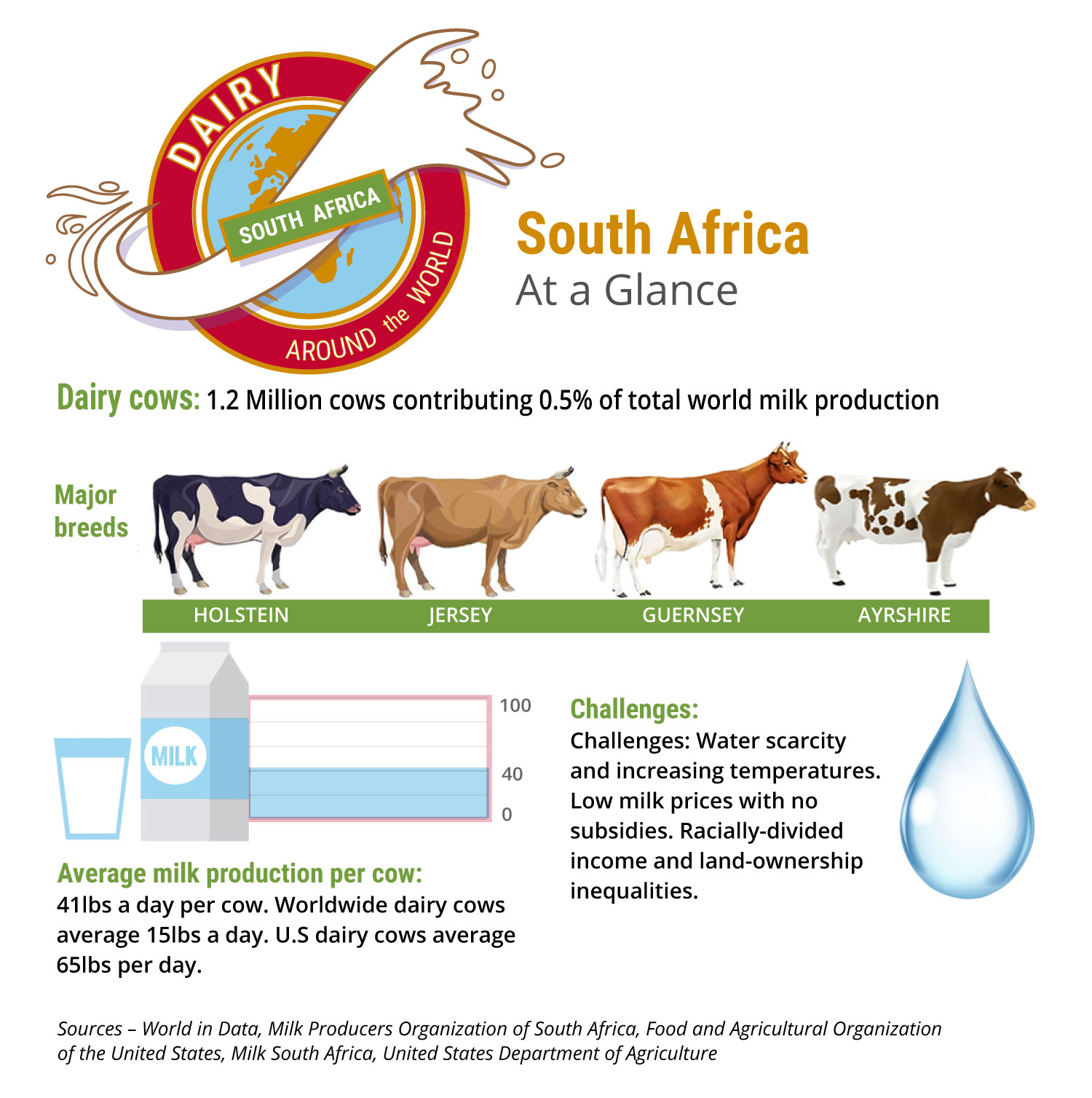

There are currently about 1200 dairy farms and 1.2 million dairy cows in South Africa, adds Bieldt, producing around 26,000 jobs.

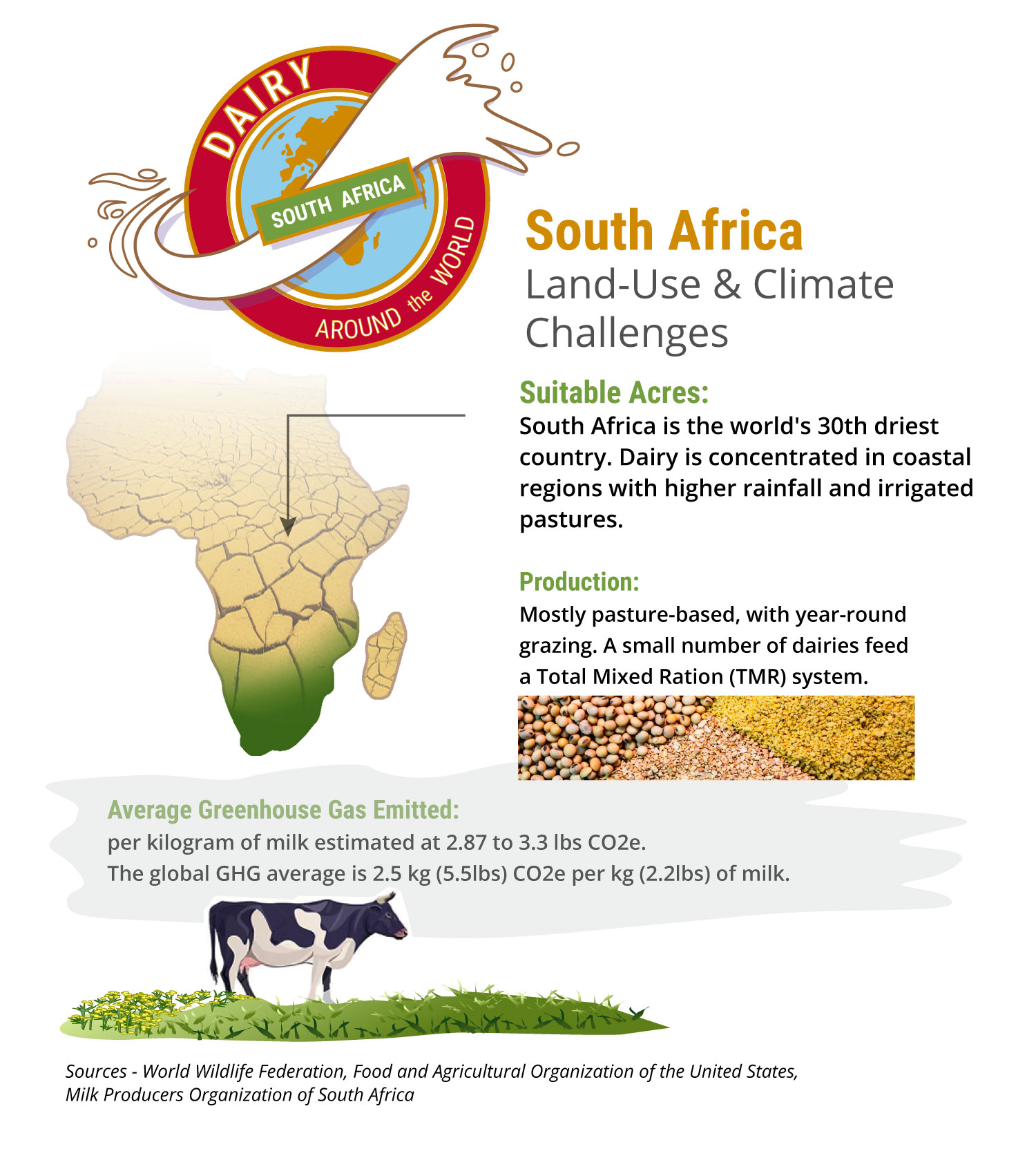

She says most dairy farms are concentrated in the south and southwest coastal provinces, where they are aided by higher rainfalls supporting pasture-based grazing systems.

Eastern Cape, Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal receive two to five times as much precipitation as the arid interior and northwestern regions of South Africa, according to the South African Weather Service.

A 2012 report by the South African Department of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries shows the three provinces account for around 75% of the country’s milk.

South Africa had the second largest average herd size in the world in 2018, according to the April 2021 LactoData report released by Milk South Africa, with the average herd of 459 cows producing an average of 18.65 liters, or 44.11 pounds, of milk daily.

(The average U.S. dairy cow produces 65 pounds of milk a day, according to 2019 USDA statistics, while the average U.S. herd size was 241 in 2018.)

But those numbers aren’t a great barometer of overall success.

Dualistic sector

South Africa’s agricultural sector overall is highly dualistic, according to a presentation at the 2015 International Conference of Agricultural Economics, consisting of approximately 35,000 well-capitalized, highly commercial white farmers producing the majority of the country’s agricultural output on 87% of the country’s agricultural lands.

Meanwhile, four million black South African farmers farm at a mostly subsistence level to feed their families, selling extra products only if they have them.

Larger, highly mechanized dairies — like the 2,500-cow Fair Cape Dairy (featured in Dairy Global) — comprised about 18 percent of the country’s total dairy farms in 2020. Thanks to superior genetics and higher input feeds, their cows produce daily yields of 35 liters (77 lbs) or more.

Almost the same percentage of South Africa’s dairies with 100 or less cows generally yield less than 10 liters (22 lbs) per cow a day.

But these are not the only systemic challenges.

The Effects of Deregulation

During Nelson’s Mandela’s presidency in 1996, South Africa completely deregulated its agricultural sectors to remove socialist controls that existed under apartheid, according to a 2010 “South Africa Farming Facts and Future Report.”

“Marketing boards were disbanded, import control was scrapped,” says Bieldt. “Overnight the farmers in this country had to contend with international competition with no protection.”

Without subsidies and no tariffs on milk imports, South African dairy farmers compete even in their own country with much cheaper dairy products from countries with milk subsidy programs.

With that stage set, says Bieldt, it is not surprising that South Africa’s “biggest challenge is that dairy farmers are price takers.” This means they have no power to regulate pricing.

Rapid innovation

On the upside, she adds, deregulation forced producers to get highly efficient, quickly.

Despite productivity gains, deregulation left South Africa’s dairy farmers at the throat of market pressures over the last few decades. As a result, more than half of dairy farms shut down between 2008 and 2018.

At the same time, per-herd productivity went up a whopping 273% per producer, according to Milk SA reports.

But low farmgate milk prices continue to be a major stumbling block.

In December 2020, the average unprocessed milk price in Europe was R6.26 (44 cents) per liter (0.26 gallons) compared to R5.19 (36 cents) a liter in South Africa, according to MPO’s most recent Lacto Data report.

Unprocessed milk in the U.S. is currently selling at the equivalent of R7.29 (51 cents) a liter (2.2lbs).

To that point, according to Bieldt, MPO is working to benchmark average milk price and production costs, giving South African dairy farmers a chance to negotiate fairer prices.

But then they have to contend with threats associated with climate disruption.

Climate Change Impact

South Africa, already the 30th driest country in the world, has been experiencing drought since 2015.

The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predicts the country will continue to undergo increasing temperatures and decreasing rainfall — which has a profound impact on South Africa’s dairy farmers=

Rikhotso says drought has been one of Amadlelo’s “biggest challenges,” pushing two of their dairy ventures to the verge of closing.

At the Fort Hare Dairy, Rikhotso explains, most of the herd is now composed of Jerseys or Friesan-Jersey crosses.

That’s because they tolerate the heat and a roughly 1.8 mile-walk daily to pasture much better than the purebred Friesans, she adds. All of Fort Hare’s 210 acres are irrigated, allowing Rhikhotso to move the herd between available pasture land.

But this too has become a problem.

Water use

With the agriculture sector fingered for using 60% of available water in South Africa, the government has cracked down, requiring all farms that irrigate to install — at their own expense — water meters that record their water usage.

They’ve also created limits on farmers’ ability to begin irrigating new acreage.

Dairy farmers weren’t thrilled about the cost of new water meter requirements, according to Bieldt, but MPO hopes more data about usage will improve conservation practices and— ultimately—increase dairy farms’ economic viability.

While South Africa’s dairies are feeling the brunt of climate-change impacts, their contribution to greenhouse gases are actually offset in large part by their pasture-based systems.

South Africa’s Dairy Greenhouse Gas Contributions

South Africa was the world’s 14th most significant contributor to greenhouse gases in 2019, according to a report by Milk SA. Seven percent of South Africa’s greenhouse gases come from agriculture.

Dairy cattle contributed 11% of the GHG production from all of South Africa’s livestock species.

But a 2020 study looking at the carbon footprint of 45 dairies in South Africa found that many dairies offset a significant portion of its carbon emissions because they are pasture-based.

On average, South African dairy farms offset their greenhouse contributions by nearly nine tons of sequestered carbon a year, significantly reducing their carbon emissions.

Seven of the farms offset all of their emissions with land-based sequestration.

Meanwhile, most of the country’s emissions contribution (80%), according to a profile by Carbon Brief, comes from reliance on coal for energy.

Still, says Simpiwe Somdyala, CEO of Amadlelo Agri: successful dairy ventures and emerging black dairy operators like Rhikhotso offer a huge opportunity to address the country’s inequalities, poverty and nutrition levels.

Extending Dairy’s Impact in Rural Communities

Community-based dairies can provide critically needed nutrition in South Africa’s most impoverished communities, Somdyala says, by selling dairy products cheaper locally and being more available than products brought in by milk retailers.

That South Africa does import a portion of its dairy products, he adds, indicates an opportunity for them to be produced within their own borders.

Even though South Africa is considered a “food secure nation,” growing enough food to feed its population, according to Oxfam, one in four South Africans go hungry regularly for lack of income.

Amadlelo works in communities with unemployment rates of around 70 percent, Somdyala says. This is markedly higher than the country’s average unemployment rate, which was 28% before the coronavirus pandemic.

But Somdyala says it has been hard to establish their farms at a profitable level because of how competitive the dairy sector is, combined with their remote locations.

Lack of market access

Amadlelo’s farms are often many hours away from markets, processors and access to other services— supplies, parts for equipment or mechanical repair shops.

Struggles to reach profitability have affected their ability to share dividends, Somdyala says with frustration in his voice. This conflicts with partner community land-owners.

Rhikhotso agrees.

“People, when they are hungry, when they start something, they want to see something to come in immediately,” Rhikhotso explains. “If they aren’t getting money immediately, they start to panic.”

On the other hand, Amadlelo employs local community members, even when it jeopardizes the farm’s cost efficiencies.

Rhikhotso oversees 18 people at Fort Hare, a large number of employees for an 800-cow herd. But, she asks, referring to Amadelo’s total 180-person workforce, “where would those people be if Amadlelo was not there?”

To truly be impactful using South Africa dairy as an empowerment vehicle, says Somdyala, the country needs to make a larger commitment to the effort.

That includes more government help, more financing and investment, better access to smart farm technology appropriate for smallholder farmers and more support from the larger South African dairy sector.

Bringing Change by Example

Bieldt paints a rosier picture when it comes to addressing post-apartheid inequalities, saying that despite their highly competitive marketplace, the South African dairy sector has long had a strong sense of “social responsibility.”

“They’re not just good businessmen,” Bieldt says about South Africa’s commercial dairy farmers, “they also have a large sense of responsibility to their community.”

Many support projects like building local schools or funding substance abuse programs, she says. Or, they mentor young up-and-coming dairy farmers.

To illustrate, she mentions Tshilidzi Matshidzula, a young Black dairy farmer from the Eastern Cape.

He received the 2020 MP Nedbank Stewardship award for turning a failing beef cattle operation into a profitable dairy farm — with help from his mentor, a successful white commercial dairy farmer.

Rikhotso says she is working hard to do her part. Ultimately, she hopes her success will attract more young black South African farmers into the industry.

“We are bringing change and that is something we are proud of,” she says. “That gives us the energy to keep growing.”

Photos: Elizabeth-Van-Papendorp, Jeanet Rikhotso

WOW. Great research and so very interesting. THANKS, Georgie.