The Daily Churn

Brazil’s dairy farmers embrace future opportunities

Brazil’s dairy farmers face challenges and embrace future opportunities

In the São Paulo region of southeastern Brazil, dairy farmer Roberto Jank Jr. has grown a successful, 5000-cow, vertically-integrated dairy business by embracing technology, high-production genetics and sustainable practices.

Jank is the director and president of Agrindus S/A, a family dairy operation that first started producing milk in 1945.

Agrindus is vertically integrated with a production factory and brand “Letti.” They produce and sell A2 milk – milk without the A2 protein, thought to be easier to digest – as well as butter, fresh cheese, yogurt and a classic South American milk-based treat, dulce de leche. They employ about 250 people across the operation.

Jank’s Holstein cow herd lives in a free-stall housing system equipped with fans, sprinklers and sand beds and are 100% fed with forages produced on 600 acres of land. Jank also breeds and raises all of their replacement heifers to make sure they restock their herd with healthy, high-producing cows.

It’s all part of a system in which “we control everything,” Jank says, noting that Agrindus has qualified for five certifications for good social and environmental practices. All this gives Agrindus the traceability to ensure a high-quality product for their consumers while controlling their costs and capturing high prices for their milk.

But while Jank’s success speaks to the potential of Brazil’s dairy industry, it’s not the current reality for most of Brazil’s dairy farmers. Only 2% of Brazilian estimated 350,000 to 400,000 dairy farmers produce more than 1100 pounds of milk a day, according to a November 2021 research article published in Animals.

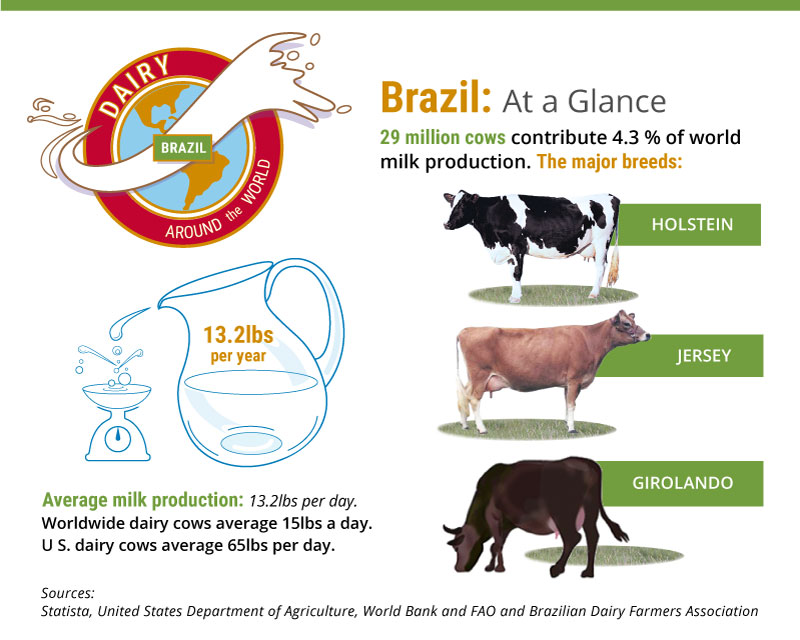

Lack of education about good husbandry practices, high-interest rates and poor infrastructure, plus a fluctuating economy keeps Brazil’s dairy sector fragmented and not yet meeting its potential, Brazilian dairy industry experts told the Daily Churn.

“The thing that best defines Brazil is the presence of contrasts. Size, knowledge, equality, everything,” says Wagner Beskow, PhD., managing partner of Transpondo, a consulting company providing educational services and logistical assistance to the Brazilian dairy sector.

The state of Dairy in Brazil

Brazil is trending toward larger, more productive dairy herds, says Beskow, but herds are “still very small.”

About 30% of the milk produced in Brazil isn’t even recorded in official counts because it is produced in remote areas and sold directly to local consumers, avoiding inspection and dairy processing facilities, according to Beskow.

Precise numbers are hard to come by. Still, according to Marcelo Carvalho, CEO of Milkpoint, an online dairy market intelligence and educational platform, there are about 350,000 to 400,000 dairy farmers in Brazil selling to about 2000 dairy processors. By comparison, the United States has an estimated 32,000 dairy farms.

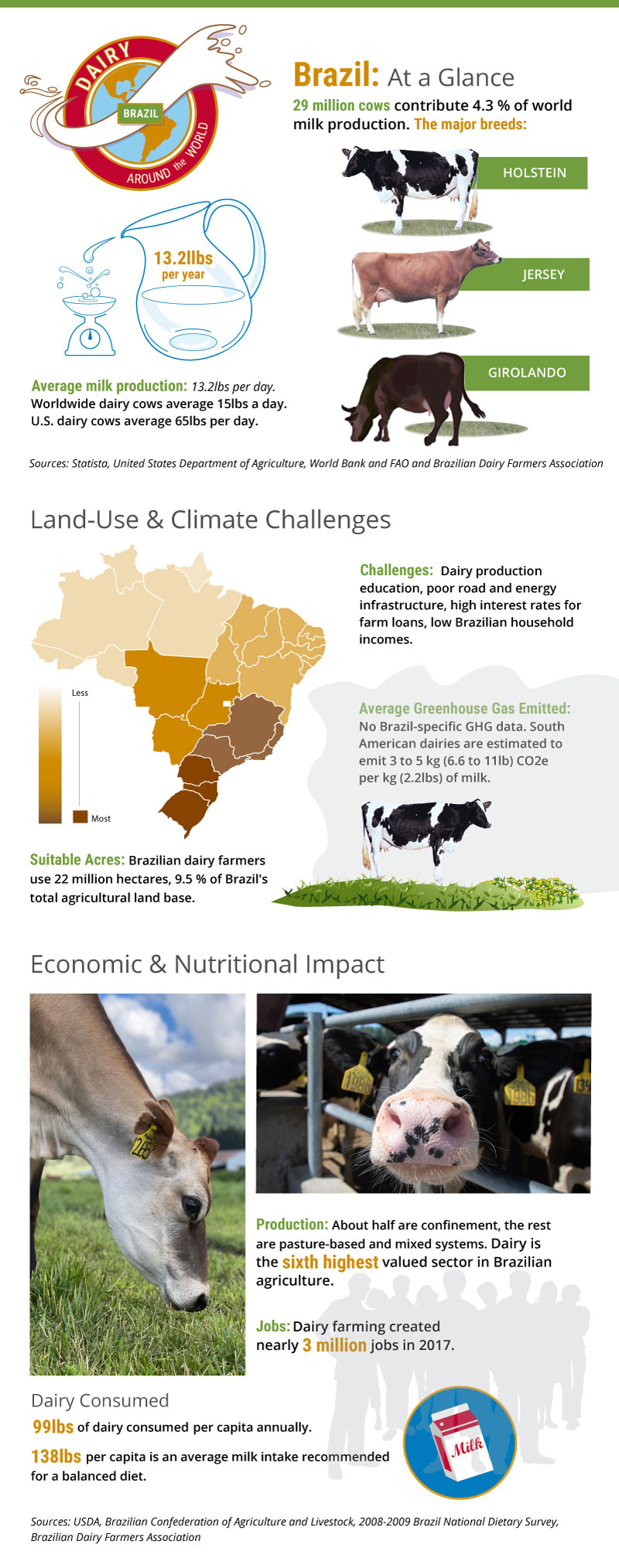

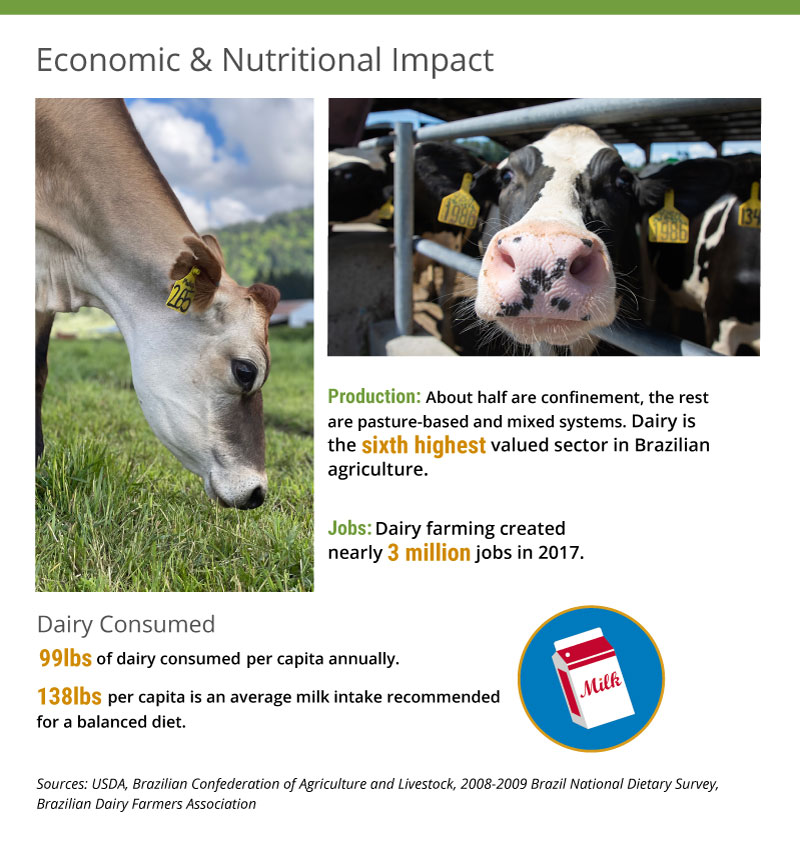

With so many dairy farms, Brazil has the third-largest dairy herd globally, with about 16.1 million cows in milk and 29 million dairy cows total as of an October 2021 report by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Brazil is also the sixth largest milk producer worldwide, producing 27.39 million tons of milk annually. The U.S. is second, following the European Union.

Dairy is a significant economic contributor to the Brazilian economy. It is the country’s sixth-highest grossing sector and generates about 3.6 million jobs, according to the Brazilian Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock.

But compared to the dairy sectors in developed nations, Brazil’s production efficiencies are lagging. The U.S., for example, has a much smaller dairy herd than Brazil, with 9.5 million dairy cows, yet produces more than four times as much milk as Brazil does, at 113.09 million tons in 2021.

Per-cow production has been increasing in Brazil since 2012; still, Brazilian dairy cows average just 13.2 lbs of milk per day, less than the worldwide average. U.S. dairy cows produce an average of 65 lbs a day.

Milk consumption has room to grow

A worker at Agrindus walks through a barn. Photo credited to Agrindus.

The Brazilian dairy sector enjoyed 15 years of growth between 2000 and 2015, directly related to a rapid rise in Brazil’s average income and dairy consumption, says Carvalho. However, that rise leveled off with a drop in economic growth during a 2016-16 economic recession.

Yet, there is an expectation that dairy consumption will take off once the Brazilian economy rights itself, according to both Carvalho and Jank.

This is a much different story compared to most developed nations, like the United Kingdom, that have experienced shrinking consumer consumption of dairy products for decades. In the U.S., per capita dairy consumption has declined for 70 years.

If the economy and buying power of Brazil’s consumers start ticking upwards again, the demand for Brazilian dairy will rise, Jank says. In addition to running Agrindus, Jank is the vice president of the Brazilian Farmers Dairy Association.

For instance, Brazilian consumers drink about the same amount of milk as U.S. consumers, but much less of the more expensive processed dairy products.

“When we get a better economy,” says Jank, “we will add a lot of cheese and yogurt that our consumers just cannot buy today.”.

Also, despite increasing milk production, Brazil is still importing roughly 3% of their annual total dairy consumption. That means there is still room for growth in dairy to meet the current demands of Brazilian consumers, Carvalho says.

With consumers’ preferences evolving, there is a future opportunity for Brazilian dairy processors willing to invest in sourcing from dairy farmers that can meet consumers’ demands for sustainable production and good animal welfare, Carvalho says.

“We have a lot of people that the main driver is price, but the next generation is much more concerned about where their food comes from,” Carvalho says. “That profile of consumer is not the same distribution as in Europe or the U.S., but those people are here.”

Brazil’s farmers are not the cause of rainforest destruction

Despite worldwide alarm over the increasing rate of destruction of the Brazilian rainforest and subsequent conversion to crop and cattle grazing land, that is not the doing of Brazil’s dairy farmers, Jank and the others interviewed by the Daily Churn say.

Brazil’s farmers follow strict land conservation rules or face the prospect of hefty fines or even criminal charges, according to Beskow.

In Brazil, farmers must set aside at least 20% to 35% of their land for native preservation.

In the most environmentally sensitive areas, like the Amazonian region, farmers have to put aside 80% of their land for native land preservation. Unlike in the U.S., there’s “no payment for preservation, it’s an obligation,” Beskow points out. Although legislation has been proposed to start compensating farmers for land preservation practices.

Jack says it’s frustrating the Brazilian farmers take the blame from the global community for environmental destruction that they don’t create and are actually actively working to preserve.

“It’s not farmers. It’s not agriculture. It’s not cattle farmers. It’s criminal people. Those people that want land that has no owner,” he says. “Selling the wood, the trees, is very good business. And they are getting land as an asset. Agriculture is just a consequence, what happens next.”

In reality, Brazil’s farmers “have a natural sense for preserving natural resources,” Beskow says. And it’s not just native habitat they are legally required to protect. For example, laws prevent farming alongside rivers or draining swamps and wetlands.

Carvalho agrees. Brazilian farmers are taking steps to improve sustainability practices, installing solar panels, pursuing regenerative agriculture practices and many dairy farmers, including Jank, have compost-bedded barns, a style of dairy housing that favors better cow health and produces compost that can be spread on the farm’s field.

Large pork and poultry farms in Brazil have led the way in manure management and capturing methane for renewable natural gas production, efforts the dairy sector is now starting to emulate, Carvalho adds.

However, there are still much more dairy farmers can do to adopt more sustainable practices.

Education for more sustainable dairy farming practices

Though current sustainability metrics for dairy production are poor with low yields per cow, the example of dairy farms like Jank’s that have developed highly productive, resource-efficient farms is testimony to the potential for Brazil’s dairy farms.

Many regions of Brazil can produce forages year-round and water is abundant. The country commands the world’s largest freshwater resource, 12% of the global total. But if production could increase, says Jank, Brazilian dairy farmers would use much less land for the same amount of milk.

Right now, Brazil’s dairy farms use 22 million hectares of land but with average milk production of an average of 1,700 liters (3474 lbs) of milk per hectare a year. Jank’s farm, however, produces 40,000 liters (88,184 lbs) of milk per hectare, nearly 25 times more than the average farm.

So, adds Jank, if Brazil’s dairy farms could increase their production per hectare by just 10 times, that would greatly reduce the amount of land needed for dairy production.

“We could borrow 20 million hectares for other crops, for other agricultural production, without cutting one tree,” he adds. “If we can just grow in average production per hectare, we can deliver a lot of open hectares.”

Beskow agrees. With better efforts to educate Brazilian dairy farmers about increasing their milk production, the sector has all the elements to improve its sustainability metrics significantly.

“We have sun. We have temperature. We have rain. We have the knowledge. It doesn’t matter if it is a confinement system or a pasture-based system, we know how to do it,” Beskow says. “But simply the information hasn’t been getting as it should to farmers.”

When dairy farmers do learn how to increase their production, it’s a light-bulb moment, Beskow says. “It’s like seeing milk coming out of the ears of the cows.”

Money and infrastructure are stumbling blocks

Beyond education, two big stumbling blocks for Brazil’s dairy farmers are poor infrastructure and high-interest rates.

While more populated regions like São Paolo, where Jank’s farm is, have made good strides in infrastructure investments, many poorer and remote areas of Brazil lack decent roads, electricity and internet services. For instance, notes Jank, farmers may not be able to run irrigation because they don’t have electricity for their pumps.

“Parts of Brazil are like California. Other parts are like India,” Jank says, categorizing the vast differences between regions of Brazil.

Beskow adds that in those less prosperous areas, roads are a significant detriment, especially for picking up milk from small producers.

“Some farms are so small it’s not viable to collect the milk,” Beskow says. “Imagine your truck traveling 50 kilometers (31 miles) to get 200 liters (440 lbs) of milk and it still gets stuck in the mud. That is very common here.”

Finding money to invest in operations is another major issue, according to Jank.

“Compared to the United States, you have a lot of cheap money to invest and long terms for investment capital. We don’t have that,” Jank says. Which means Brazil’s dairy farmers don’t have funds to invest in more efficient buildings, milking parlors or equipment.

Beskow agrees.

“The credit card interest rate is above 300% per year,” he says. “You want to make money in Brazil, come as a banker.”

Bright future for dairy in Brazil

Unlike other agricultural sectors in Brazil, which are already becoming competitive internationally, dairy has yet to see the same success. But the potential is there, says Carvalho.

The Brazilian deregulation of dairy in the 1990s supported the free market.

This led to fragmentation in the marketplace, like much higher milk prices for larger, more efficient dairy farms with higher volume. That in turn has contributed to pushing smaller dairy farms that couldn’t compete out of business, according to Carvalho.

Labor has also become a problem as more Brazilians have left rural areas for better economic opportunities in the cities. Still, Brazil’s natural resources and potential economic growth point to a bright future for the dairy sector.

“Milk is a sector with the most profound transformation going on today. Many are leaving, which may be a social problem, but the production is not going down. Changing production systems and increasing scale of productivity is all happening at a fast pace,” Carvalho says.

“Challenges are still big, but I see there is potential to become a big (international) player and exporter at some point in the future.”