The Daily Churn

UK dairy farmers face upheaval

After a lifetime of building up a thriving, pasture-based dairy business in Northern England, farmer Robert Craig worries about the sector’s uncertain future.

U.K. dairy farmers are embroiled in trade upheavals and new environmental regulations prompted by Brexit, the U.K.’s voter-mandated exit from the European Union (EU), Craig tells the Daily Churn. Plus, they are reeling from continuing Covid-19 pandemic supply chain breakdowns, labor shortages and increasing scrutiny from a small but vocal group of anti-dairy critics.

Craig, 51, started dairy farming with his father in the 1990s when EU milk quota rules were in effect—and it was a struggle.

“We had a really lousy milk quota of about 200,000 liters, which was just about enough for 35 to 40 cows,” Craig adds. “It was a tough life, really tough. We weren’t big enough to make any money.”

But after the quota was abolished in 2015, Craig grew his dairy business. He now employs 20 people and milks 1500 cows split between three farmsteads in the picturesque regions of Northumberland and the Lakes District.

Craig is also vice-chairman of the member board of trustees for the Royal Association of British Dairy Farmers (RABDF). Given the challenges cited, he says he foresees the continuation of farm closures that have plagued the dairy sector for the last several generations.

As of 2020, there were 11,900 U.K. dairy farms, a 67% reduction since 1995 when there were 35,700 dairy farms, according to a U.K. Parliament House of Commons Library research brief. In 1950, there were 196,000 U.K. dairy farms.

“If I were to predict,” says Craig, “I would say in the next 10 years, we’ll be down to about 6000 dairy farms but will probably produce about the same amount of milk (as today).” The data we gathered seems to support this prediction.

State of the UK dairy sector

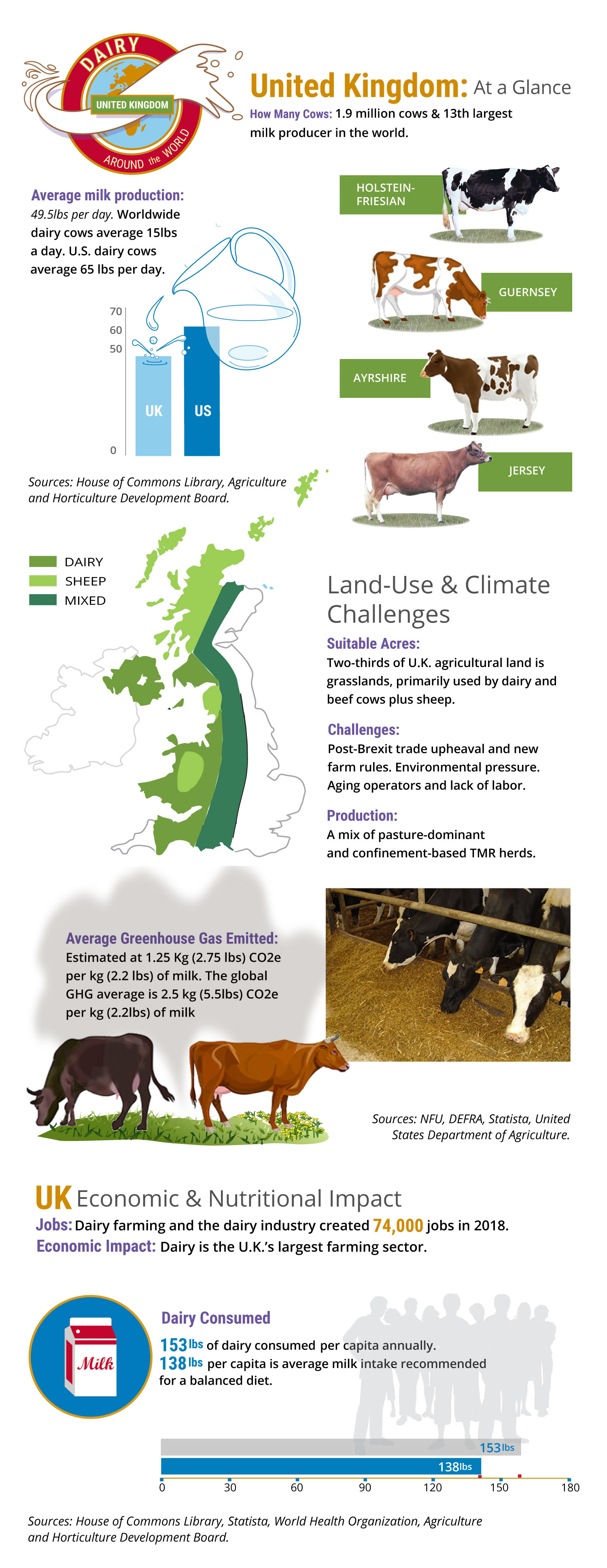

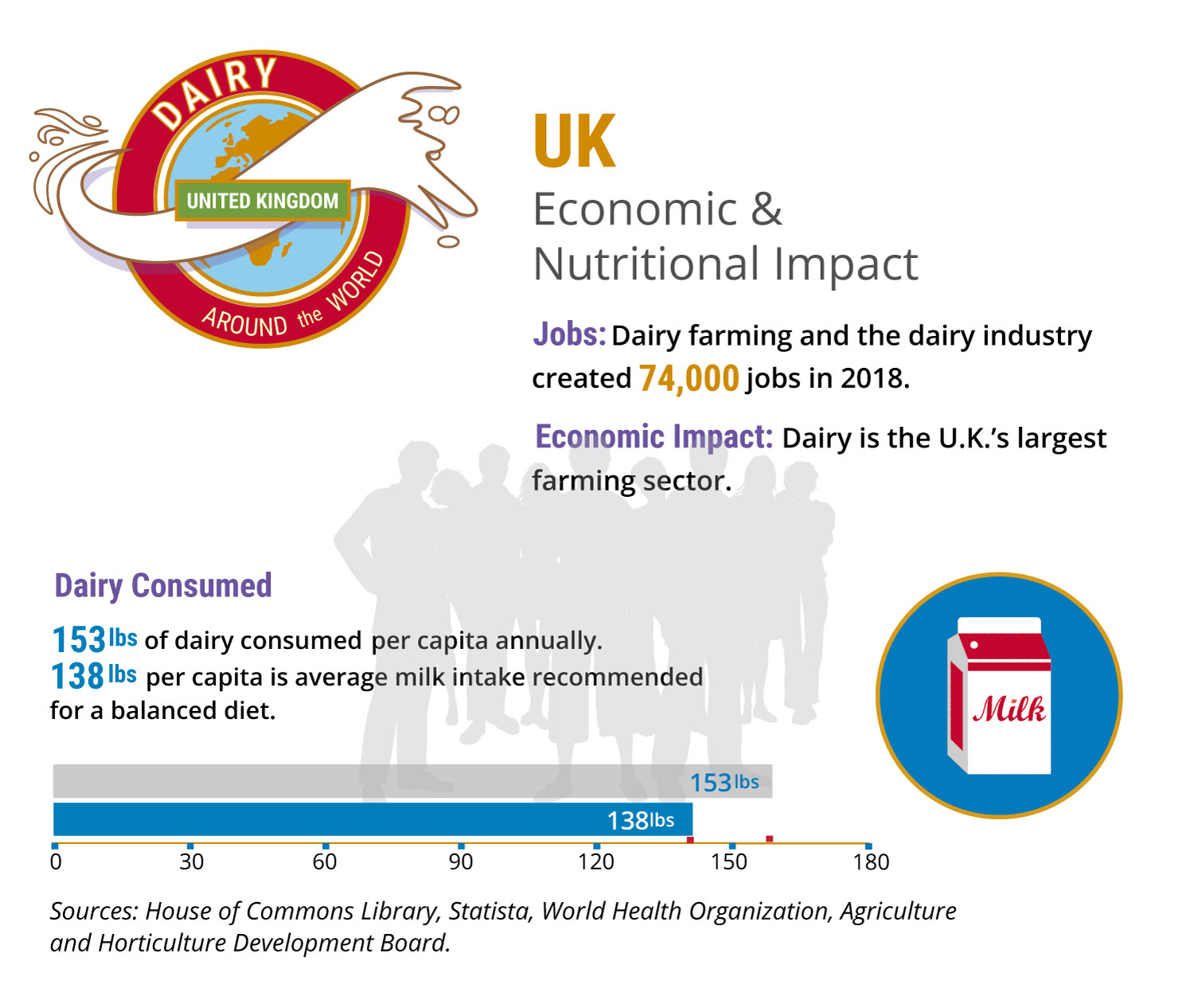

Dairy is the U.K.’s largest agricultural sector, contributing about 16.4% of the country’s total agricultural output in 2020.

They are also the world’s 13th largest milk producer, though Brexit has taken a toll on exports. According to the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB), trade disruption and red tape caused by the EU exit, combined with pandemic lockdowns, contributed to 11% lower dairy exports in the first half of 2021 compared to 2020.

Also, similar to other developed nations, the U.K. dairy herd size has shrunk while milk production has increased. In 2020, the total U.K. herd size was 1.9 million cows, a 28% reduction since 1996. Yet with fewer dairy farms and cows, in 2020, the U.K. still produced the most milk since 1990 — about 33 billion pounds.

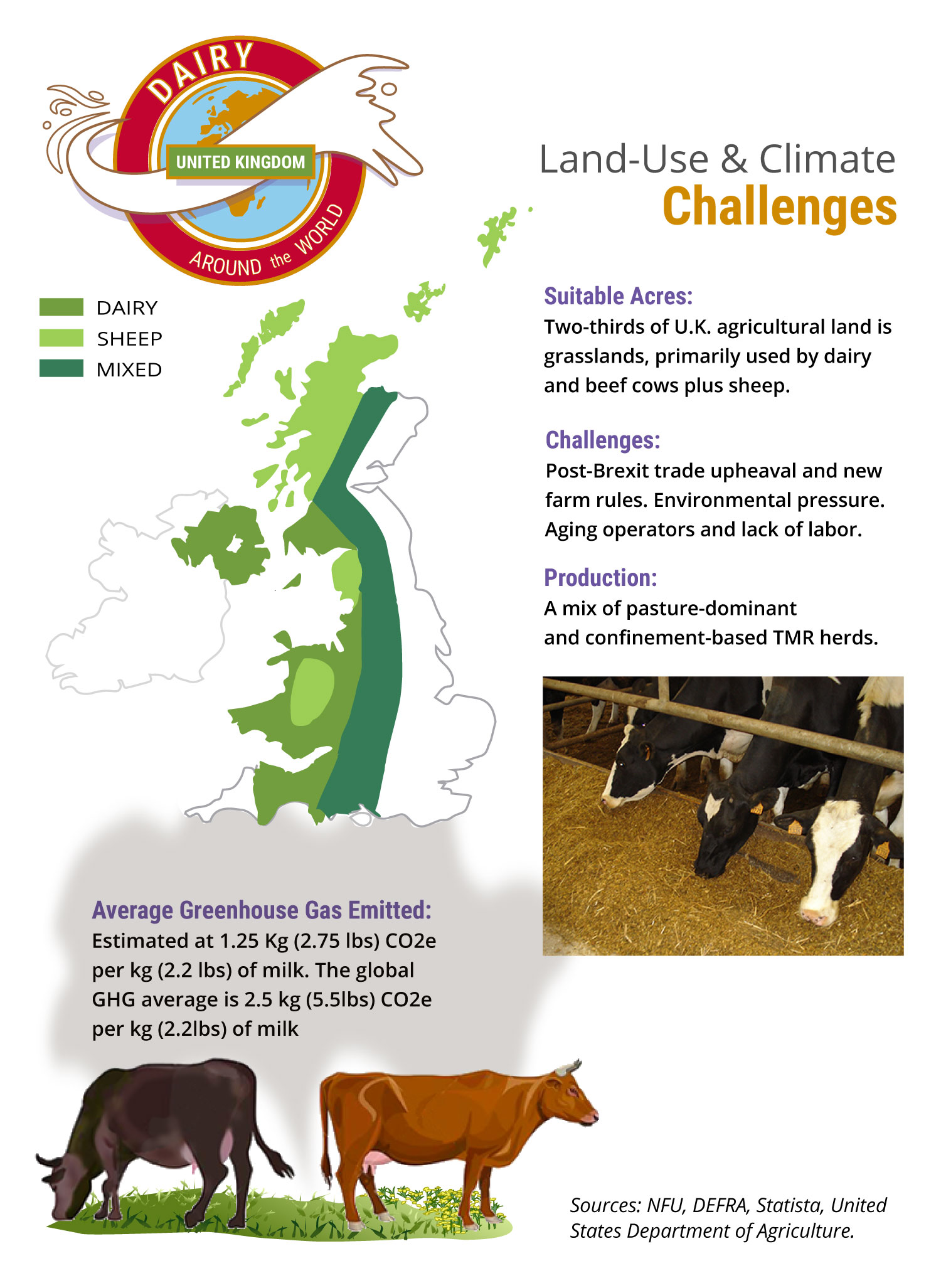

According to the House of Commons Library research brief, shrinking herds hit Scotland and Wales hardest, with 50% of Scottish and 40% of Welsh dairy farms shuttered between 2008 and 2018. Remaining facilities vary in type and size.

Craig says about one-quarter of U.K. dairy farms (representing approximately 50% of the total cows) are considered large, confinement-style farms feeding Total Mixed Rations (TMR) diets.

The rest are smaller, primarily pasture-based farms that have grown their businesses the way he has: increasing overall operations with new locations, but keeping herd sizes relatively low. Craig has about 500 cows each at his three locations.

But with new environmental regulations already being imposed and more coming soon, combined with fundamental changes proposed to the U.K.’s long-standing farm subsidy program, things will likely change for the country’s dairy farmers, according to Craig and others.

Right now, the worst part is the uncertainty, says Jude Capper, PhD., livestock sustainability consultant and part-time professor at Harper Adams University, a U.K.-located agri-food university.

“We don’t know what’s happening with imports. We don’t know what’s happening with exports,” she says. “We don’t know what the implications are in terms of the changes (farmers) are going to have to make or not, and whether that’s going to change things with (subsidies).”

A nature-based subsidy scheme for UK dairy farmers

How subsidies are awarded to U.K. farmers is shifting in the post-Brexit era in favor of environmental outcomes.

Under the EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), U.K. farmers received an annual subsidy. In 2018, that amounted to around £3.5 billion ($4.71 billion), according to the Institute for Government.

With CAP no longer in effect due to Brexit, the U.K. government is creating new agricultural policies, which includes eliminating subsidies over the next seven years. Instead, they plan to pay farmers for undertaking actions to improve the environment under a new program called the “Environmental Land Management Scheme” (ELMS).

Implementation of ELMS is expected to begin in 2024.

This year, the government started pilot programs to sign up U.K. farmers. But, so far, only 500 have agreed to do so, says Rhian Price, livestock editor for Farmers Weekly, a leading U.K. farming publication. Farmers are nervous about the new program, she says, and are not convinced they will see any of the promised money.

Price and her husband are also dairy farmers, managing 160 cows on a tenant farm in Shropshire County close to the Welsh border.

“A lot of farmers voted for Brexit because they wanted less red tape,” she adds. “They’re not signing up for the scheme because they’re going to be policed even more heavily.”

Even if producers aren’t on board with ELMS, they will still face new regulations.

Under a new Clean Air Strategy, dairy farmers will be required to reduce their ammonia emissions. Currently, 87% of U.K. ammonia emissions come from agriculture; 23% come from dairy specifically.

And in the spring of 2022, “Farming Rules for Water” mandates will start to take effect. U.K. farmers will only be allowed to spread manure if they can show their soil needs the nutrients to support their crop needs. Or if there is no pollution risk.

“Obviously, that is a huge problem for dairy farmers,” says Price. “What are they going to do with slurry that is already stored?”

Meanwhile, U.K. farmers are dealing with more immediate issues.

Labor crunch and high supply costs

A dire shortage of labor and high supply costs, attributed to Covid and post-Brexit implications, are also contributing to dairy farmers’ woes.

Traditionally, Eastern European migrants filled U.K. farm jobs. But now it’s more complicated for those workers to enter the country. Nor have pandemic lockdowns helped.

A winter 2020 survey by RABDF found nearly a third of dairy farmers were considering leaving the industry due to lack of labor. Craig says it’s been particularly hard for large-scale dairy farms.

“We’re desperately short of labor,” he adds. “We just don’t have the migrant labor that we’ve become, as an industry, heavily reliant upon.”

A big part of the problem is the lack of young U.K. residents interested in entering dairy, according to Welsh dairy farmer Patrick Holden, who is also CEO of the U.K.-based Sustainable Food Trust.

“We can’t get the young people to get up early in the morning and milk cows,” he says, adding that young people who do wish to return to agriculture want to work on more “ecological, diverse farm environments.”

Feed costs have also increased, says Price, and disruptions in other sectors have had a trickle-down effect. For example, gas shortages shut down fertilizer plants, doubling fertilizer costs since last year.

To make the situation even more dire, says Price, until recently the average cost of production was outpacing farmgate milk prices. Although that appears to be shifting.

“Some of the milk contracts still aren’t meeting rising costs,” she says. “But everyone is hopeful that companies are going to be announcing new milk prices this autumn.” And then there’s consumer perception.

Climate change and consumer perception

The entire dairy sector should be working together to promote a more positive image of the U.K. dairy industry, many of the people we interviewed said.

Dairy has been demonized by a small but vocal group of anti-livestock activists, Craig continues, but the accomplishments of the U.K. dairy sector have been largely ignored in the press.

“So often where you hear a debate or an advert or whatever about climate change, (they say) one of the easiest things you can do is change your diet, reduce or eliminate dairy,” he adds. “That’s become an accepted narrative now, which is, of course, false.”

Greenhouse gas emissions are a global concern in the face of climate change. But the worldwide dairy sector, including milk production, processing and transportation, contributed just 3.4% of the world’s total of nearly 50,000 million tons of greenhouse gas emitted in 2015.

Even so, the U.K. dairy sector has taken strides to reduce its emissions impact. According to the 2018 Dairy Roadmap report, U.K. dairy farmers reduced their total greenhouse gas emissions by 24% between 1990 and 2015. In addition, 70% of U.K. dairy farmers have worked to reduce their emissions and 43% currently produce or use renewable energy.

But this message of environmental improvement doesn’t always reach consumers, according to Craig. He cites how UK dairy farmers have halved their antibiotic use as one example of how dairy’s progress has been overlooked.

The “rewilding” movement — an effort to return agricultural lands to native conditions — has been a particularly frustrating conflict between U.K farmers and consumers, Capper adds. Some big-name celebrities in the U.K. have come out to support rewilding, including Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s wife.

“People just simply don’t get that if we want sustainable food, we want it at relatively low cost; if we don’t want it to be imported, we can’t turn all of our farmland into a play park.”

Despite all the current turbulence, Craig and the others interviewed by the Daily Churn do see reasons for hope.

Hope for the future

Holden hopes the new subsidy system rewarding good farm practices will change the economic dynamics of the current dairy sector in favor of a more economically-sustainable future.

“At the moment, we’re all trapped. We’re following the money. More cows, you keep them inside, you feed them grain, you get more money,” Holden says. “It’s been a race to bottom with more intensification, larger and larger herds. Who is winning? No one.”

U.K. milk consumption — which has been shrinking for decades — was reinvigorated by the Covid-19 pandemic and a shift toward locally-produced goods.

“We have a lot more consumers shopping local, asking questions about where their food is coming from and buying nicer quality food,” Price says. “It bodes well with the future. (Dairy farmers) need to capitalize on that and keep that momentum going.”

Plus, new international focus on dairy farmers’ ability to sequester carbon could end up being a “win-win” for pasture-based dairy farmers, Craig says. Especially considering that with a temperate, wet climate, most of the U.K. is well-suited to pasture-based dairy farming.

He hopes it will end up being a boon in the long-term.

“With the focus more on carbon now, the economics are going to change,” Craig says. “Maybe that will be the catalyst to curb the further decline in (dairy farm) numbers and keep things more stable.”